414 barriers to doing business in Venezuela

The state of the sanctions program and options for the dollar

Venezuela coverage has been wall-to-wall and nobody knows what’s going to happen next. An excellent habitat for talking heads. Perhaps the oil companies will go in, we’ll pay for the oil with dollars, custodied by the U.S. Treasury, which can only be used to buy… washing machines made in Ohio?

On Friday, in a meeting with oil executives, the CEO of EXXON called Venezuela “uninvestable.” The Halliburton CEO admitted that they left in 2019 due to sanctions. Before any American companies return to Venezuela, they’ll first demand clarity and guarantees on the lifting of sanctions. This is only rational.

Amid the chaos, I always find it best to go back to stats and fundamentals. Instead of trying to gauge what the U.S. will do, let’s take a look at the structural barriers to doing anything: the sanctions on Venezuela and what might happen to them.

An economy in distress

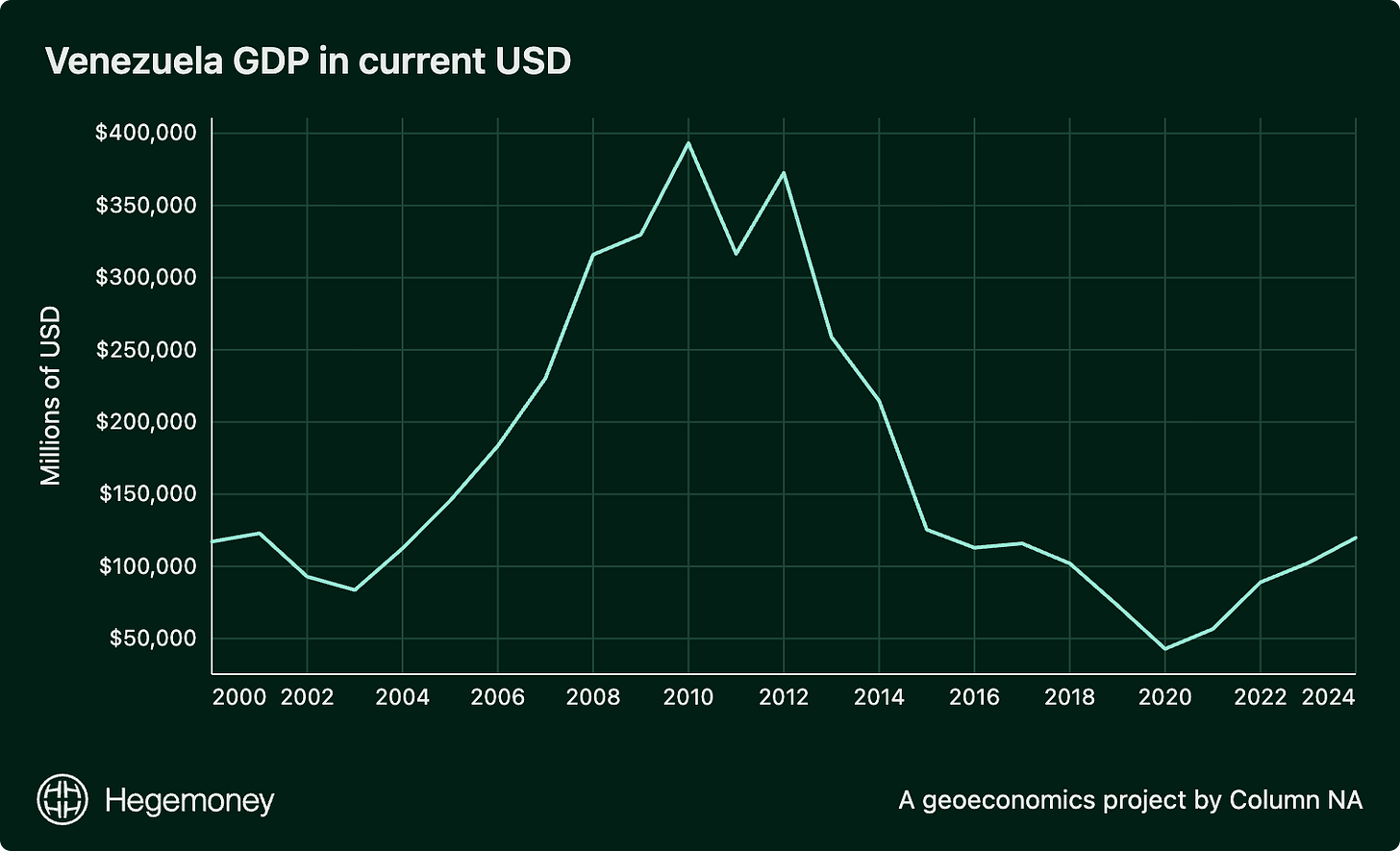

The Venezuelan economy has been in distress for quite some time, even before the most restrictive sanctions were imposed. Famously, in 2017 there were reports that citizens were breaking into the Maracaibo zoo to eat the animals because of food shortages. Eating stolen zoo animals should be a legitimate crisis indicator. At its peak, average annual inflation hit over 65,000 percent in 2018, according to the IMF. By the time OFAC designated PDVSA (the state-owned oil company) in 2019, Venezuela’s GDP had already fallen from a peak of $393B in 2010 to $102B at the end of 2018, according to World Bank data.

The 414

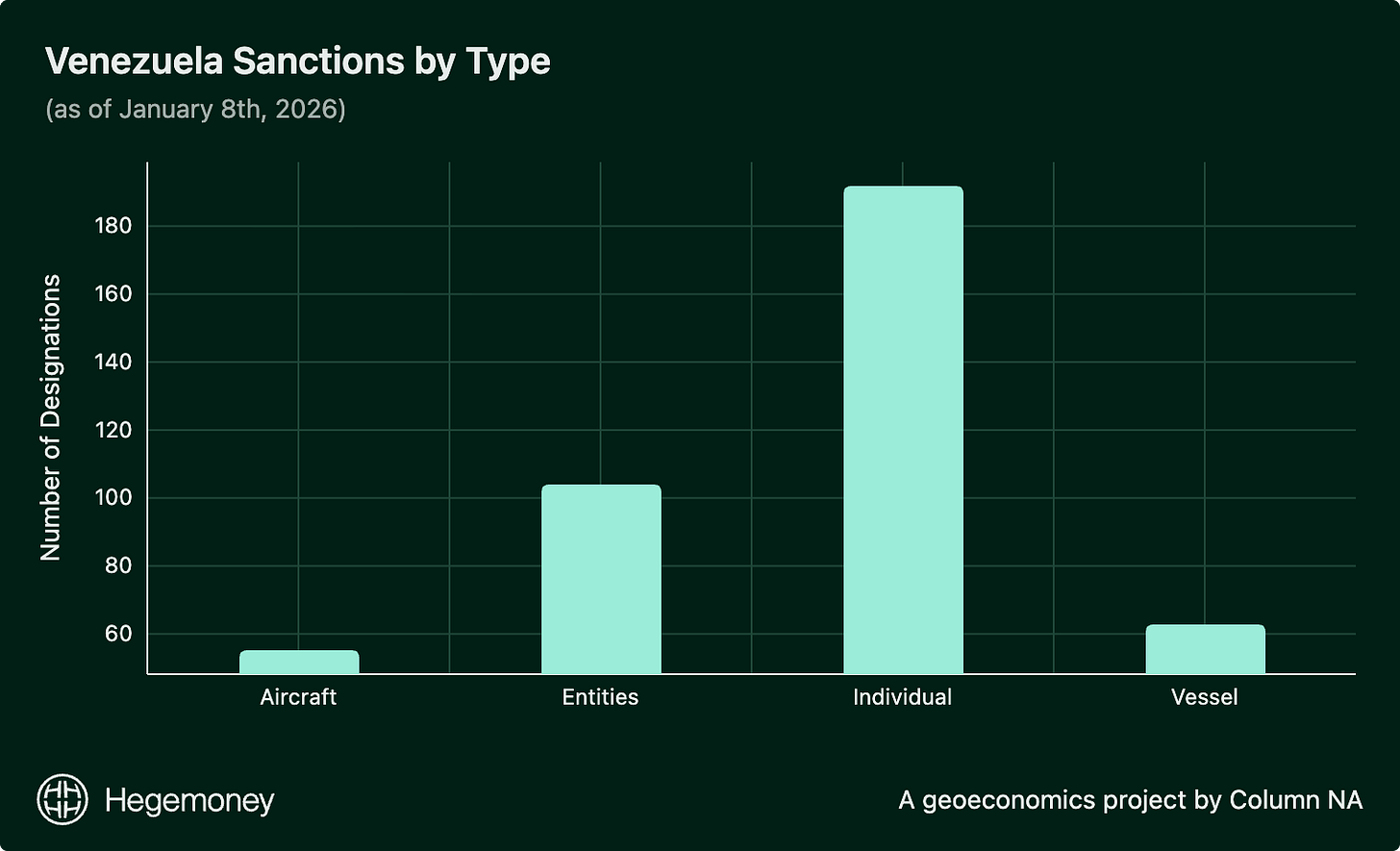

Looking at the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s (OFAC) SDN list, 414 names are currently sanctioned. That’s a combination of aircraft, entities (companies, institutions, government agencies), individuals, and ships.

The escalation ladder

In order to impose sanctions, OFAC relies on legal authorities from either executive orders or public laws1. After Nicolás Maduro came into power in 2013 and cracked down on democratic rights, Congress passed the Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act in December of 2014. Seven executive orders against Venezuela followed.

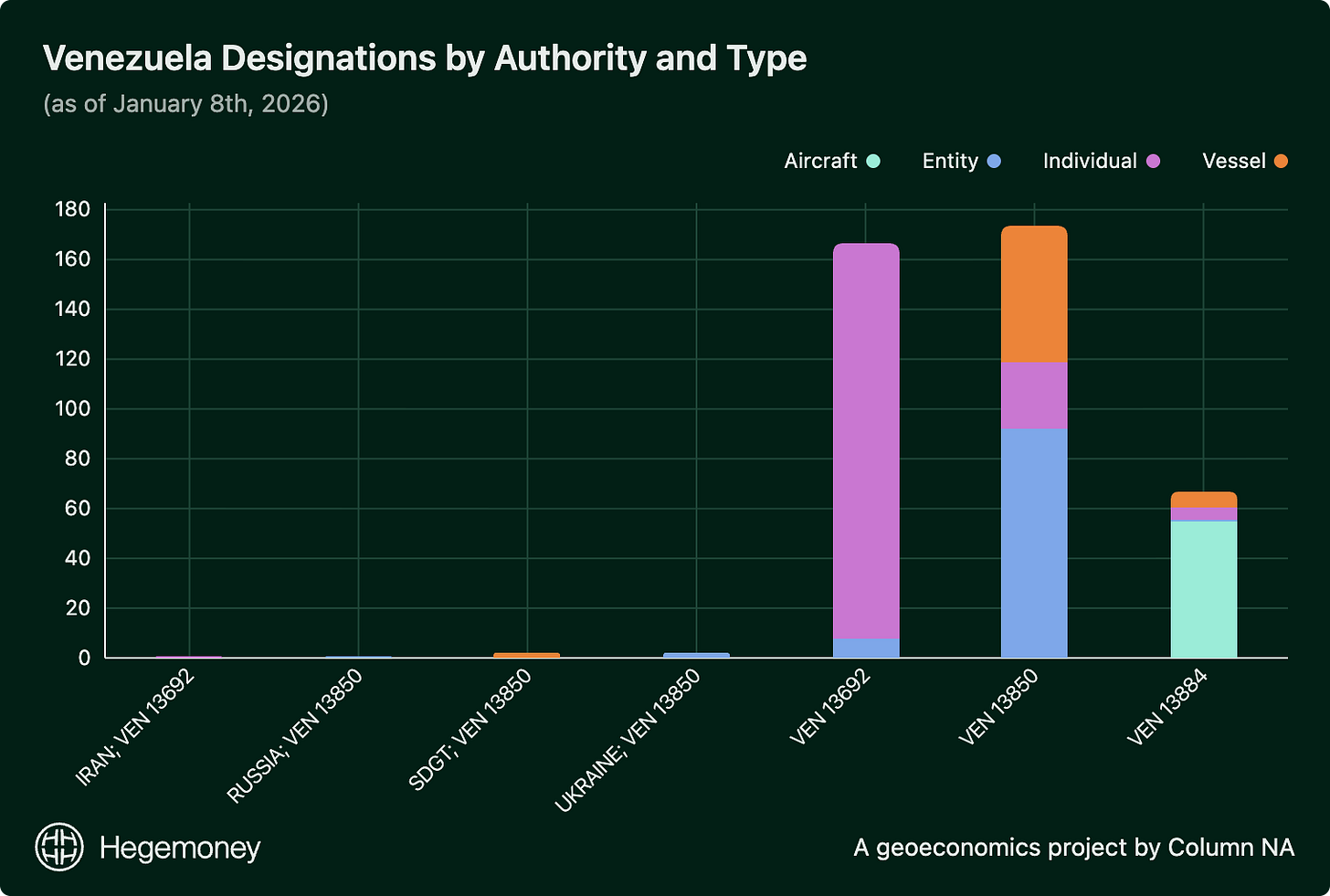

The first designations happened in 2015 under Executive Order 13692 targeting violators of human rights and democracy. Prior to 2015, there were no financial sanctions on Venezuela. The executive orders have grown in reach and severity as the situation in Venezuela has worsened. Here is a quick(ish) rundown:

Can I please see this in a chart?

I am so happy you asked. This chart summarizes which EOs were used the most. In some cases OFAC will use multiple authorities (under multiple sanctions programs) to designate an entity. This makes it significantly more difficult for them to be removed from the sanctions list. Most vessel designations are under EO 13850 (oil sector), but recent seizures (Dec 2025–Jan 2026) often use hybrid counter-narcotics/terrorism authorities for international waters enforcement.

Licenses as safety valves

Sanctions are enormously costly for the target country. Nicolas Mulder’s book Economic Weapon notes that the Allied blockade in WWI contributed to 300,000–400,000 people dying of starvation in Central Europe. OFAC tries to avoid these sorts of tolls against civilians by conducting impact assessments to figure out what licenses (general or specific exemptions) are needed to mitigate the impact of sanctions. Russia’s sanctions program has the most active general licenses. Venezuela is in second with 27 active general licenses (GLs) and 16 expired. A general license (GL) essentially permits certain types of activity to anyone who qualifies. Depending on the nature of the request, OFAC, (usually) in consultation with the Department of State, will also issue specific licenses to applicants, but those aren’t publicly disclosed, pursuant to the Trade Secrets Act.

Licenses can be confusing to navigate (which leads to lots of over-compliance and refusals to do business even in non-designated sectors) and the Venezuela programs specifically have seen short windows of permitted activity followed by fast removals. For example, in October of 2023, General License 44 permitted oil and gas operations for 6 months. Which is absurd — what company would invest in decrepit oil infrastructure for only 6 months at great cost? So it was extended for another month and never renewed after May 2024. Not tenable.

Chevron is probably the best-known example of a general license. They got a GL to resume limited oil production in November 2022. In early 2025, they were ordered to wind down operations within two months. Then in late March 2025, Chevron got another license which told them they could extend the wind-down until the end of May 2025 (an extra two and a half months). Lots of back and forth. This all makes it understandably difficult for U.S. companies to commit to serious capital investments.

Outside of the oil sector, licenses in Venezuela tend to fall in the following categories.

A path to securing a place for the dollar

In Venezuela, the United States has gone from enforcing sanctions through banks to enforcing sanctions through tanks (well, ships, but that doesn’t rhyme). While this satisfies the administration’s aims on sanctions adherence, it won’t provide Venezuela the serious economic relief it needs to rebuild and eventually allow the U.S. to take the country out of, how should I say this, conservatorship. While sanctions weren’t the sole cause of Venezuela’s economic collapse, they have become increasingly severe and certainly a major contributor to economic distress. The country cannot move forward without sanctions relief. Here are some thoughts:

Lift certain sanctions: The U.S. has to balance economic leverage on the regime with access to goods and services. The government may want to consider a more targeted strategy that lifts sanctions on sovereign debt or affiliates of PDVSA. For example, Monómeros is a Colombian fertilizer company whose majority owner is Pequiven, Venezuela’s state-owned petrochemical company. Pequiven itself is a subsidiary of PDVSA, Venezuela’s national oil company. Monómeros had a specific license to sell its products which was not renewed. In my opinion, commercial activity related to agricultural production should be allowed — we should be issuing licenses, with long time horizons, to permit this sort of activity. The U.S. government could also think about providing comfort letters to vetted foreign partners of the U.S. in certain sectors to share the burden of rebuilding the economy.

Communicate what is open: Confusion over licenses makes American companies hesitant to invest in Venezuela. The U.S. needs to put out a clear and transparent guide for how to reenter the country. This way, while U.S. energy companies rebuild the carbon infrastructure, other U.S. companies can help rebuild domestic infrastructure like roads, schools, and hospitals. The economy has been a mess for over two decades. Ambiguity about sanctions will keep U.S. commercial interest focused on oil — which alone can’t give Venezuela the help it needs.

Provide tools to access USD: Venezuela has probably patched together a financial system through black-market cash from oil sales, limited offshore banking, and a shift to crypto. The U.S. needs to provide the Venezuelan banking sector with real access to USD, and OFAC should issue targeted general or specific licenses for U.S. correspondent relationships with non-sanctioned private Venezuelan banks. The U.S. government could also turn to existing general licenses as templates for limited debt/bond relief tied to reforms.

Give U.S. companies guarantees on timelines: U.S. oil companies have already come out and said that they need strong legal and financial guarantees to re-enter Venezuela. These companies have the technical capabilities and resources to rebuild infrastructure in Venezuela, but they are also public corporations who must answer to shareholders — the U.S. government needs to promise a minimum 2-year timeline for an initial phase of investment, with potential guarantee of financial compensation if the policy changes.

Mandate goods be denominated in USD: Nearly 100 percent of export invoicing in the Americas is done in U.S. dollars, but we can assume that Venezuela’s share has deteriorated because of lack of access to USD. We should give the financial sector access to the dollar, BUT mandate that sanctions relief is attached to their use of the dollar in export invoicing. If Venezuela truly has the world’s largest reserves of crude oil, this is a rare opportunity to reinforce dollar supremacy in commodity pricing by mandating that the export of that oil is done in USD.

I was recently struck by how quickly and comprehensively we lifted sanctions on the (new) Syrian government earlier last year. The head of the Syrian Central Bank hailed the repeal as a “miracle.” The Venezuelan government appears ready to cooperate with us. They should have an opportunity to manifest the same economic miracle.2

Executive orders related to Venezuela have also been pursuant to the International Economic Emergency Powers Act, the National Emergency Act, and the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Upon submitting material for prepublication review by the government, I was directed to add the following (obvious) disclaimer: All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the US Government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US Government authentication of information or endorsement of the author’s views.

Love the comparison with Syria lifting. Super intrigued by sheer volume of EOs for the program, but also that the use of each appears narrowly scoped. I can’t imagine doing the same bar chart for Russia/Ukraine.

I like your chart format.