The dollar belongs in the National Security Strategy

A 38-year oversight ends

Well, it appears that the Trump administration is serious about executing its National Security Strategy.

So… I went back and looked at every National Security Strategy (NSS) since the report was mandated in 1986 by the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act (people say I’m fun at dinner parties). The NSS is a regular report the President sends to Congress. It basically lays out the big picture: what the U.S. is worried about, what our top priorities are, and the administration’s game plan for keeping the country safe and prosperous.

Our research is focused on the dollar, so part of this audit was to see how this administration is speaking differently about the currency’s role vs. previous administrations.

I assumed there would be mentions throughout the years of how the U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency is one of our main instruments of foreign policy and a national priority to maintain — especially after 9/11, when Treasury leveraged the financial system to counter terrorism and isolate the axis of evil. I found references to the importance of a healthy American economy (references which slowly morphed into the importance of a strong world economy after the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997). And I found talk about the need for open financial markets to ensure prosperity. I certainly found a lot of palaver on free trade and building up international financial institutions. There was even mention of the importance of sanctions as a tool of national security.

But as for any direct acknowledgment of the dollar’s reserve status as a core national security interest… nothing.

Of course, U.S. officials have highlighted the dollar’s reserve status over the years in speeches, op-eds, and testimonies. Yet the dollar’s centrality to American power projection was never codified in the NSS itself.

Until 2025.

What Are America’s Available Means to Get What We Want?

The world’s leading financial system and capital markets, including the dollar’s global reserve currency status;

Say what you will about the merits or demerits of the self-titled “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine” and the rest of the document, but the fact that this was the first time the NSS has explicitly tied the dollar to national security is notable and echoes longstanding bipartisan thinking.

It is about time.

The dollar belongs in the NSS. Again, for years, policymakers across administrations have treated the dollar’s role as a strategic asset in practice and generally done what is necessary to maintain its status.

Think about the fundamentals of a reserve currency: deep and liquid financial markets, economic heft, robust institutional credibility, military and diplomatic relationships. Over the past 25 years, despite recurring concerns that the renminbi or euro might eventually surpass the dollar, the United States has largely maintained these core pillars. However, on two elements central to supporting network effects — access and infrastructure — we have moved slowly and fallen behind. And it shows.

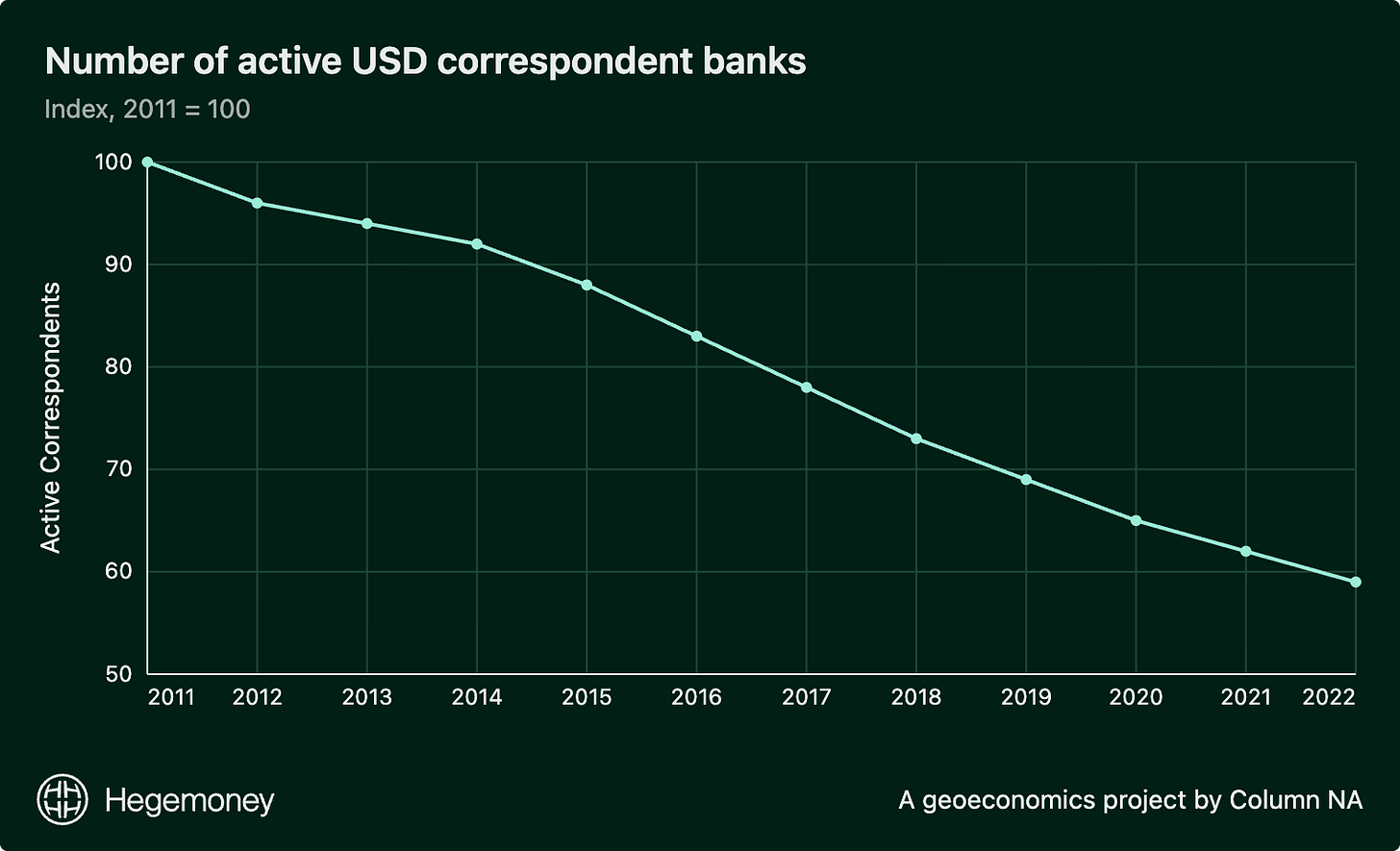

U.S. regulations have made it prohibitively expensive (and fraught on the compliance side) to distribute our payment systems in foreign markets, leading to American banks’ retrenchment from emerging markets. From 2011–2022, the number of USD correspondent banking relationships fell between 30 percent and 76 percent across regions — particularly sharply in areas like the Pacific Islands — according to a BIS study conducted with SWIFT. Though there has been a trend in de-risking across different currencies, USD correspondents have seen the deepest reduction.

Stablecoins have taken center stage as the leading candidate for next-gen cross-border payments, the largest being managed by a private issuer domiciled and operating outside the U.S., using American safe-haven assets to back its currency.

While China piloted a retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) and led mBridge — the most advanced cross-border wholesale CBDC — the U.S. spent years dithering about whether to participate.

[Obama voice] Let me be clear. There is no single challenger to the U.S. dollar right now. The threat is from the rising use of a basket of currencies, which chip away at the dollar’s role in aggregate. This will not happen tomorrow, and that is the problem. The glacial nature of this issue has allowed our policymakers to ignore threats to the dollar. We assume infinite dominance in financial markets and are failing to take active measures to ensure the dollar’s global role. We are suffering from the hubris of permanence.

So what can be done?

I don’t know who wrote the NSS, but someone in the administration seems ready to take action. Either that or they are just paying lip service, which would make me a very, very sad economist :( If the administration is serious, they can start with a few concrete policy steps to shore up the dollar:

Amend the GENIUS Act: The GENIUS Act is a step in the right direction. However, allowing foreign private stablecoin issuers to benefit from the stability of our financial system, without equivalent promises to safeguard that financial system, is shortsighted. An amendment should demand that if a foreign issuer holds U.S. treasuries in its reserves and operates outside the U.S. market, it must comply with U.S. AML/CTF and sanction requirements. This is already par for the course for foreign banks leveraging USD correspondent relationships. Fair access to American markets should come with fair responsibility.

Burden sharing with U.S. financial institutions: Heavy fines in the 2010s spooked banks and led to a wave of de-risking, which significantly reduced dollar access globally and forced countries to turn to alternative settlement mechanisms. For many banks, simple compliance risk/reward calculations led to the abandonment of some jurisdictions, such as the Pacific Island Countries, many of which are strategically significant to national security. The government should partner with American banks to support national policy aims by returning to strategic jurisdictions. U.S. banks propose a plan. The USG approves it. Both parties monitor risk: if deemed too risky, the U.S. firm exits without penalty.

Understand our adversaries’ alternatives: U.S. economic diplomats overseas should actively engage foreign commercial partners — banks, fintechs, and central banks — to understand if and why they’re adopting alternatives like China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System. This needs to be a systematic information-gathering effort. By feeding these insights back to Treasury, Commerce, and the Fed, the government can develop countermeasures, like targeted incentives for using dollar-based infrastructure. It is worth noting that the NSS specifically states that U.S. embassies should be promoting American businesses, and there is a bill sitting in the House that creates an Office of Strategic Currency Diplomacy within the State Department, which would be an ideal steward for a task like this.

Continue to lead on standards for distributed ledger tech (DLT) platforms: If the U.S. isn’t going to pursue a CBDC, we need to ensure that our preferred method for cross-border payments can still integrate with CBDC systems. One way to do this is to lead on standards. The International Standards Organization’s (ISO) committee for blockchain and distributed ledger has 12 established standards published and 22 under development, including an interoperability framework. ISO doesn’t disclose who contributes to which standards, but given that China is a participating member, they have likely nominated experts to work on this standard to ensure their DLT-based platforms like mBridge and e-CNY are connected.

The challenge now is to translate rhetoric into actions that reinforce the dollar’s advantages and address emerging threats. Equally challenging will be promoting the dollar against the backdrop of twin deficits, attacks on the Fed, and an unpredictable tariff regime that could make foreign users of the dollar question our institutional credibility.

As proven by last weekend’s actions in Venezuela, the U.S. is no longer hiding its hand. The 2025 NSS puts the dollar where many have long believed it belongs: at the heart of U.S. national security planning. That sends a signal to the world, yes, but also to domestic policymakers that claiming the dollar as a national security asset will require treating it like one, including maintenance, fresh paint, and judicious use.1

Upon submitting material for prepublication review by the government, I was directed to add the following (and fairly obvious) disclaimer: All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official positions or views of the US Government. Nothing in the contents should be construed as asserting or implying US Government authentication of information or endorsement of the author’s views.

The dollar’s problems are the inevitable result of fiat money, chronic deficits, and interventionist policy. Twin deficits signal fiscal excess that can only be sustained through inflation or debt monetization, while attacks on the Fed miss the deeper issue: discretionary central banking itself erodes trust by distorting prices and misallocating capital. Tariffs further weaken the dollar’s international role by restricting trade and shrinking real demand for the currency. From this perspective, foreign skepticism toward the dollar reflects rational doubt in U.S. institutions, and no amount of rhetoric can restore confidence without genuine fiscal restraint and an end to monetary manipulation.

Solid writing and impressive insight