The euro in the thunderdome

How Europe might try to globalize its common currency

A strange fact about the euro is that a euro in a German bank isn’t quite the same as a euro in an Italian bank — despite both being Eurozone countries. This is essentially a failure of the European economic bloc to fully integrate, but, after the Battle for Greenland, the Europeans appear to be rethinking their position.

Let us cast our gaze to Davos, where Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s speech earned its place in history as the most articulate global recognition that the world has ruptured from the post-Bretton Woods rules-based international order and become… something else. Carney had previously called it a “new world order.” We are obviously not going to call it that. German Chancellor Merz called it “an era of great power politics.” One can imagine an international relations textbook dubbing it the age of “principled pragmatic polarity.” The White House might simply call it “THE THUNDERDOME.” All have their merits.

Carney’s speech called for “middle powers” to apply the same standards to allies and rivals, build new institutions rather than awaiting the old order’s revival, and reduce vulnerability to coercion through strong domestic economies and diversified international ties. Personally I read it as a call for fewer dependencies.

I wouldn’t hold my breath that our allies are sitting around waiting for the U.S. to wind the clock back to 2015. The Battle for Greenland seems to temporarily be on ice (ha!), but the Europeans are vocal about reevaluating their relationships, dependencies, and vulnerabilities. Or, as Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank, put it, “[we’re] going to do a big SWOT analysis.”

And with that analysis, we should expect the Europeans to try to assert a greater international role for the euro.

Second best

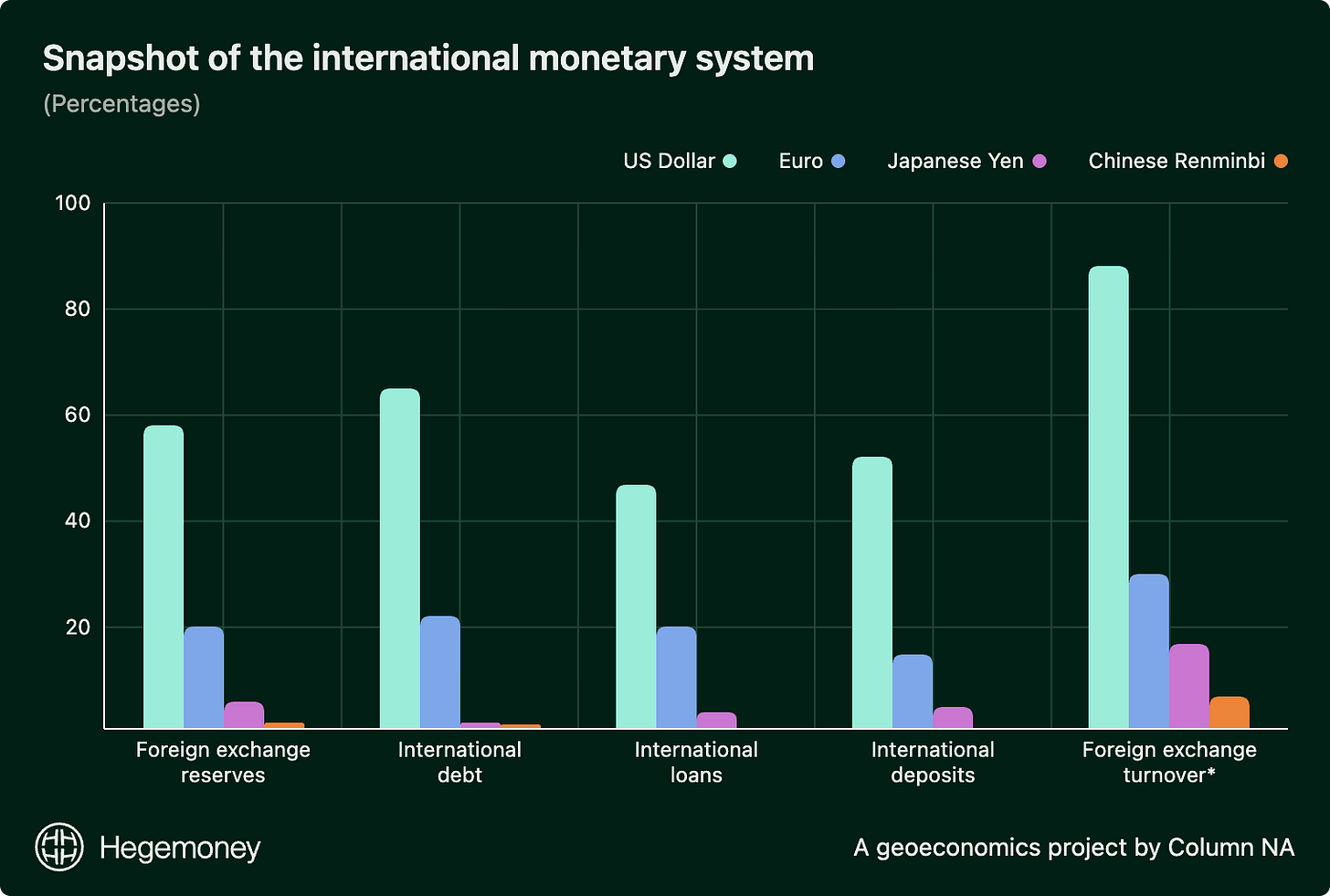

Upon its launch in 1999, the euro was hailed as the first major rival to the dollar since the greenback replaced the sterling as the world’s dominant currency after WWII. A former boss of mine called the euro “Europe’s answer to war on the continent.” And while it has helped prevent war between members, both politics and the lack of a fiscal and financial union have held the currency back from leveraging the heft of the European bloc to become the top global currency. Thus the euro sits in second place and by quite a large margin.

Necessity is the mother of invention

Alexander Hamilton said it best. “A national debt, if it is not excessive, will be to us a national blessing; it will be a powerful cement of our union.” The Eurozone never federalized its debts; the Germans looked at the Greeks and said, nein danke. All the European national governments still own their respective debts and budgets, despite sharing a single currency.

But despite reluctance to loosen grips over their national accounts, one thing has motivated Europe: crisis. Crisis is the one thing that can push the Europeans out of their comfort zone and toward greater integration.

The Europeans are well-motivated by existential threats.

Eurozone Debt Crisis (2009–2012)

This crisis exposed deep fractures in the Eurozone. Mario Draghi, then President of the European Central Bank, promised to do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro. Integration measures followed, notably the Fiscal Compact, the European Stability Mechanism, and talks (that eventually stalled) on debt mutualization and Eurobonds.

The debt crisis also gave birth to the Banking Union (2014) and the Capital Markets Union (2015), which helped centralize banking supervision, break the loop between banking risk and sovereign risk, and make Europe’s financial system less fragmented and more resilient.

Rise of U.S. Unilateralism (2016–2019)

Frustrated by Trump’s unilateralism — especially the U.S.’s 2018 withdrawal from the Iran deal (JCPOA) and reimposition of sanctions on Iran — President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker declared “the hour of European sovereignty” in his State of the Union address, calling for the euro to become the instrument of a more sovereign Europe. This led to an announcement from the European Union titled, “Towards a stronger international role of the euro,” and the 2019 launch of INSTEX — a kind of clearing house — by France, Germany, and the UK to enable non-dollar trade with Iran. This was a notable defiance of U.S. financial hegemony in the modern era. (INSTEX was dissolved in 2023.)

COVID-19 Pandemic (2020)

The pandemic came as a severe shock, exposing eurozone weaknesses and accelerating demands for fiscal solidarity and digital payments. In 2020, EU leaders agreed on the €750 billion NextGenerationEU fund with joint debt issuance — the first major step toward debt mutualization and fiscal union. Lockdowns also drove a shift to digital payments, prompting the ECB in October 2020 to formally investigate creating a digital euro to bolster monetary sovereignty and reduce reliance on foreign digital systems.

Signposts that the EU may actually be serious about a global euro

Davos is over, but the Battle for Greenland will leave a sour taste in Europe’s mouth. Disagreements over European integration have hamstrung the euro but fears of territorial loss and economic coercion can make neighbors become friends real fast.

The euro is unlikely to replace the dollar anytime soon — the European Union combined is still only the second-largest economy in the world by nominal GDP and not all countries in the bloc use the euro. However, we’re watching for steps the Europeans could take to materially chip away at the USD’s position.

Finalizing European deposit insurance (EDIS): Insured deposits at European banks are only guaranteed by the country in which the deposit is held. This is one of the reasons why a euro in an Italian bank carries different risks than a euro in a German bank — building a Eurozone-wide deposit scheme would solve this by making deposits truly fungible. Though this third pillar of the Banking Union remains stalled, post-Davos calls for unity could trigger a plenary vote on recommendations like one in the 2024 EU Committee report, which proposed exploring loans to national deposit guarantee funds as a precursor to full deposit insurance.

Pursuit of a Common Asset: Eurozone bond markets just aren’t deep enough to provide a serious alternative to the deep and liquid capital markets of the United States. The numbers prove it: the entire Eurozone has approximately $14 trillion in sovereign debt, compared to the U.S. with $31 trillion. European defense spending, which rose 11% in 2025, could increase the supply of national bonds as governments look to fund budget increases, but that doesn’t fix the lack of a mutual safe asset.

The NextGenerationEU bonds were a historic step toward debt mutualization — some called it Europe’s “Hamilton moment.” The last distribution from those bonds is being made this year, and any further issuance would be worth watching. If the Eurozone is serious about improving the role of the euro, it has no choice but to deepen the pool of euro-denominated safe assets through a mutualization framework.

Accelerating the digital euro: The ECB recently finished the prep phase for a digital euro and has moved to the technical build-out. If legislation passes in 2026, pilots could start mid-2027, and be ready for issuance by 2029. A digital euro would enhance monetary sovereignty and reduce reliance on foreign payment systems, making it clear that while the U.S. is promoting privately-issued stablecoins as a cross-border solution, the Eurozone will not outsource monetary infrastructure to a private company or the United States.

A digital euro would provide a sovereign digital settlement asset that includes many of the functional features of a stablecoin without the private credit risk.

Providing incentives to settle trades in euros: The EU is the top trade partner for 72 countries, giving the Eurozone some under-appreciated negotiating heft. Global infrastructure is designed for dollar settlement, but the Eurozone could provide incentives for settling transactions in euros instead. For example, the EU’s new carbon border tax (CBAM) forces importers to pay for emissions on carbon-intensive goods (steel, cement). The bloc could offer favorable terms or reduced costs if the entire transaction for carbon-heavy goods is settled in euros. We should look out for the introduction of more incentives — or an improvement in euro liquidity in trade finance — to accelerate euro-denominated trade.

Pricing commodities in euros: In 2018, then European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker noted that it seemed absurd that the EU imports its energy in dollars. The EU might try to challenge dollar hegemony in energy markets by increasing liquidity on European exchanges for commodity derivatives — specifically through longer trading hours, new euro-denominated derivatives (e.g. liquid hydrogen or liquid natural gas benchmarks), and CBAM-linked incentives (see above).

Expanding euro swap lines: The ECB maintains standing bilateral swap lines with major central banks: the Federal Reserve, Bank of Canada, Bank of Japan, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, and the People’s Bank of China. The ECB also maintains other temporary or precautionary liquidity lines with various non-euro area central banks for crisis support. Strategically expanding swap lines with key trading partners would also support use of the euro as a vehicle currency.

Until a euro in an Italian bank is the same as a euro in a German bank, Europe’s favored currency will always be a distant second. The U.S. has long benefitted from the slow economic integration of the European Union, but under the thunderdome, we may not be able to rely on intra-European squabbling for much longer.1

For the handful of countries that are in EU candidate status - should they be pushed to adopt the euro as a requirement for joining?

How should the European Union be thinking about its member countries that are not in the eurozone (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden)? This accounts for ~20% of the bloc's economic output, but they retain their own national currencies.